Monolingual reference electronic corpora in the translator’s toolbox the Google Books “Corpus” and BYU corpora

Источник: https://theopenmic.co/monolingual-reference-electronic-corpora-in-the-translators-toolbox/

Greater than 9 minutes, my friend!

What is the Google Books Corpus and what is it meant to be used for?

The Google Books Corpus (GBC) has been available since 2011 and contains linguistic data based on the famous, now legal, Google Books project. The “corpus” is massive, as it contains 500 billion words of texts written between the 16th and the 20th centuries, in English (361 billion words), French (45 billion words), Spanish (45 billion words), German (37 billion words), Russian (35 billion words), and Hebrew (2 billion words), as is explained in a Science article that presents the Google Books Corpus. As is emphasized by the authors of the article, 80 years would be required if you wanted to read the books published in the year 2000 only, and “the sequence of letters is one thousand times longer than the human genome: if you wrote it out in a straight line, it would reach to the moon and back 10 times over”. No less! Hard not to be impressed.

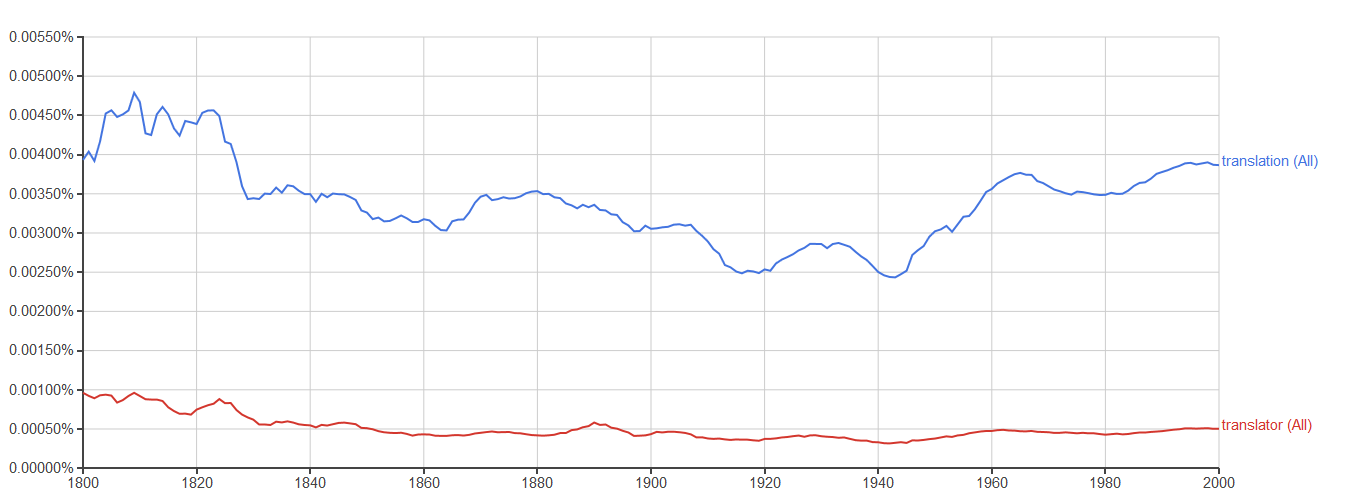

The way you can use the GBC is through its very user-friendly Ngram Viewer: you can search for one or several sequences made of 1 word (translation), 2 words (translation training), 3 words (best translator ever), etc. These sequences are called n-grams (1-gram, 2-gram, 3-gram, etc.). You can then get in barely one second very nice graphs that show the evolution of the frequency of the n-gram(s) that you are interested in. To take one example, the graph below shows the frequencies for the words “translation” and “translator” between 1800 and 2000.

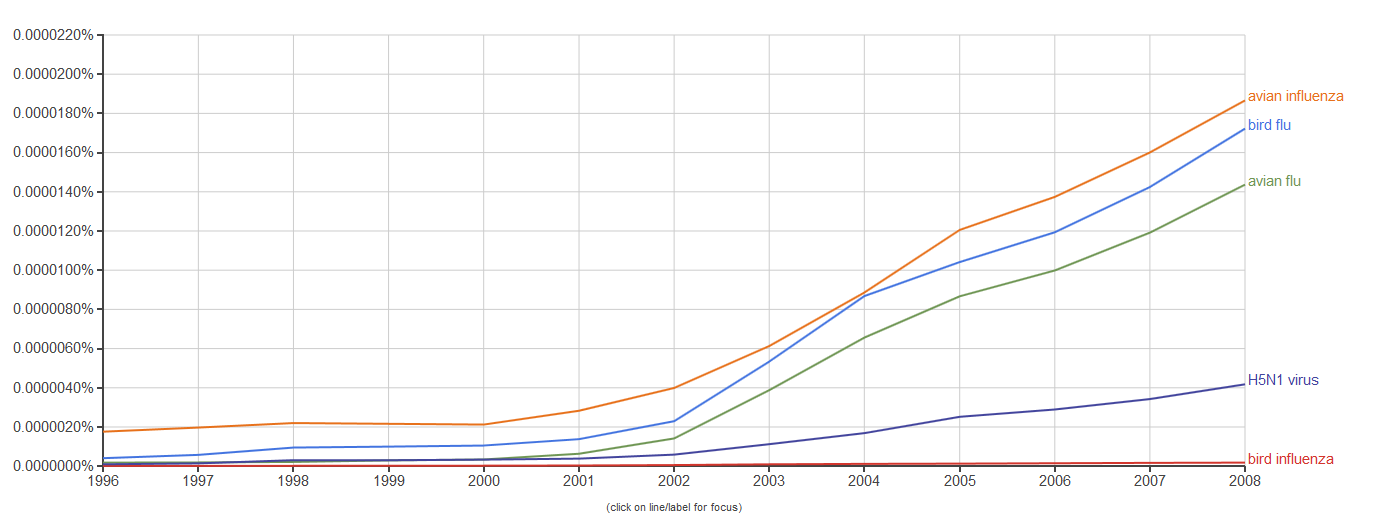

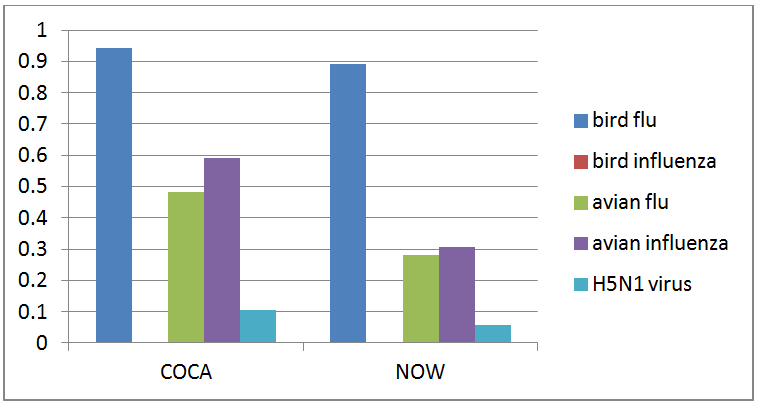

There are thus many things you can search for (see a list of – often fun – examples here or here, which include graphs of what people say they drink, and show that people today seem to love their country more than their husband/wife, their job or their mother… Wait. Is that serious? See below). So you might think that you can use the tool to find out information on terminology, phraseology, or grammatical constructions thanks to such a huge database. For instance, you could compare the use of “bird flu”, “bird influenza”, “avian flu”, “avian influenza”, and “H5N1 virus” these last 20 years (although note that you cannot go further than 2008), which all refer to a specific kind of virus endemic to birds, and see that not all of them are used with the same frequency. Professional translators and terminologists often value such usage-based information.

However, there are a few problematic issues when you want to use the GBC for linguistic purposes. As a translator, you might want to collect information on the use of a technical term, an expression or even a grammatical construction, either to improve your understanding of the source text or to increase the naturalness of your translation and improve your invisibility for high-quality translations. The problem is that the data contained in the GBC do not make it a reliable tool for such questions. Not enough information is provided about the source of the linguistic data used to calculate the frequencies of n-grams: have the texts been written by native speakers? By specialists of the field? To what registers do the data belong: literary, scientific, academic, press…? Are some of the texts translations? What about geographical variation? All these pieces of information are crucial when it comes to checking lexical or grammatical usage. Also, it is always interesting to be able to take a look at the context where n-grams appear and the GBC n-gram viewer does not really allow that in a user-friendly way, although you have the possibility to switch toGoogle Books at the bottom of the page.

I would say the tool is more cultural than linguistic, and that is exactly what the title of the Science article mentioned above says: “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books” (underlining mine). The authors associate the GBC with “culturomics”, which they define as “application of high-throughput data collection and analysis to the study of human culture.” It is true that the GBC does provide its users with quick and interesting results on the frequencies of textual elements, and at a time when the big data revolution reaches a lot of different fields, we can see that journalists, linguists, historians have started using the GBC (or other electronic corpora) to try and uncover cultural and/or linguistic trends. Yet, some newspaper and magazine articles have started to question the use of the GBC as a linguistic tool, see here, here, or here. A very nice scientific contribution to the debate is also provided by Eitan Adam Pechenick, Christopher M. Danforth, and Peter Sheridan Dodds with their article “Characterizing the Google Books Corpus: Strong Limits to Inferences of Socio-Cultural and Linguistic Evolution”. It is true that journalists in particular have taken the use of the GBC a bit too far: the most surprising hypothesis I have read so far comes from an article from The Washington Post published in October 2015 and entitled “How Hipsters May be Bringing Back Vintage Language”. According to the article, hipsters (yes, hipsters) are responsible for the resurfacing of, I quote, “archaic words” like amongst, whilst, parlor, smitten, or perchance. This claim is illustrated by searches performed on the Google Books Ngram Viewer, searches whose results do show a post-2000 upturn with higher frequencies for such words. However, it seems a bit far-fetched to claim that this is a “hipster phenomenon”: the GBC provides absolutely no way of knowing whether the data have been produced by authors belonging to the hipster sociotype, and once again, not enough information is provided about the source of the data to make any valid claim with enough confidence – it would be interesting to see whether the texts in the GBC are evenly distributed as far their degree of formalism is concerned, for instance.

So what’s the alternative?

There are much better tools out there for linguistic analyses, accessible easily and freely within a limited use. On the website of the Brigham Young University (BYU) in the United States you can find a very nice interface set up by Professor Mark Davies which provides you with many different kinds of electronic corpora (see screenshot below). There you will find the very well-known British National Corpus (BNC), which contains 100 million words of spoken and written English for different registers, and Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), which contains 520 million words of spoken and American English for different registers, but also third-generation corpora like the News On the Web corpus (NOW) and its 3 billion words extracted from web-based newspapers and magazines published from 2010 to the present day (as it is an “open corpus”, new data are added all the time, 4 million words each day), the Corpus of Global Web-based English (GloWbE) and its 1.9 billion words of English in all its geographical varieties, or the Wikipedia Corpus and its 1.9 billion words extracted from 4.4 million Wikipedia articles. (You will also find other corpora for other languages and other registers on the BYU webpage, but I will stick to so-called “general” English for this blog post. Other English-language corpora available elsewhere on the web are (among others) Monco, the Aranea Corpora, or the Leeds Internet Corpora).

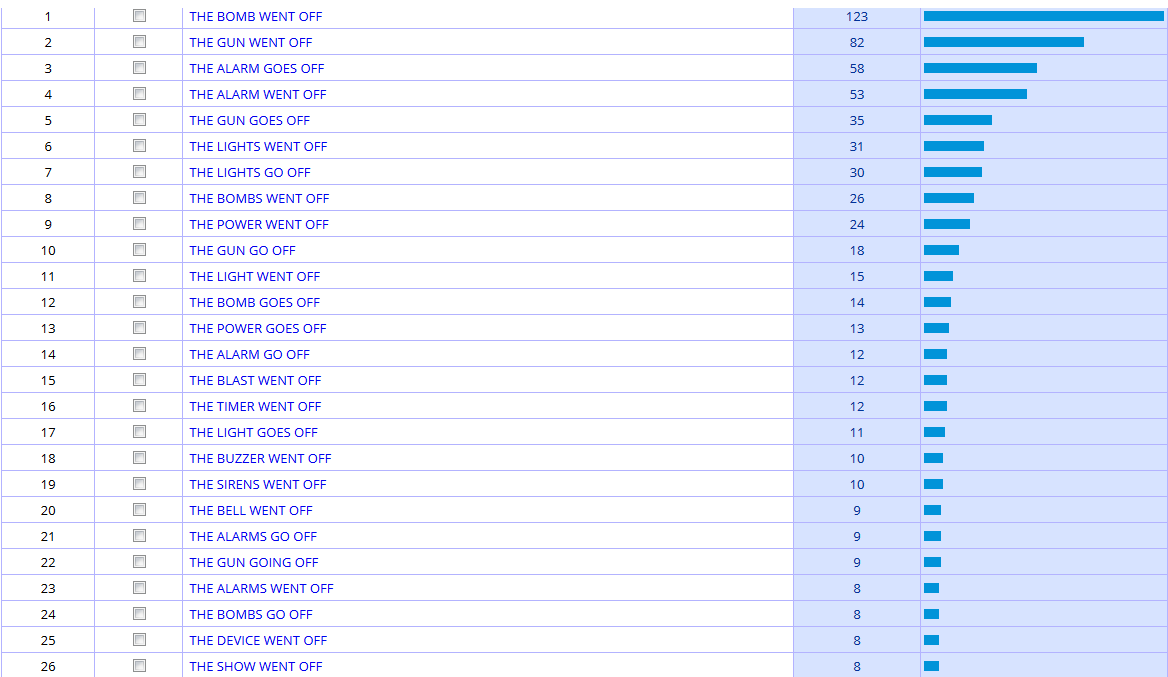

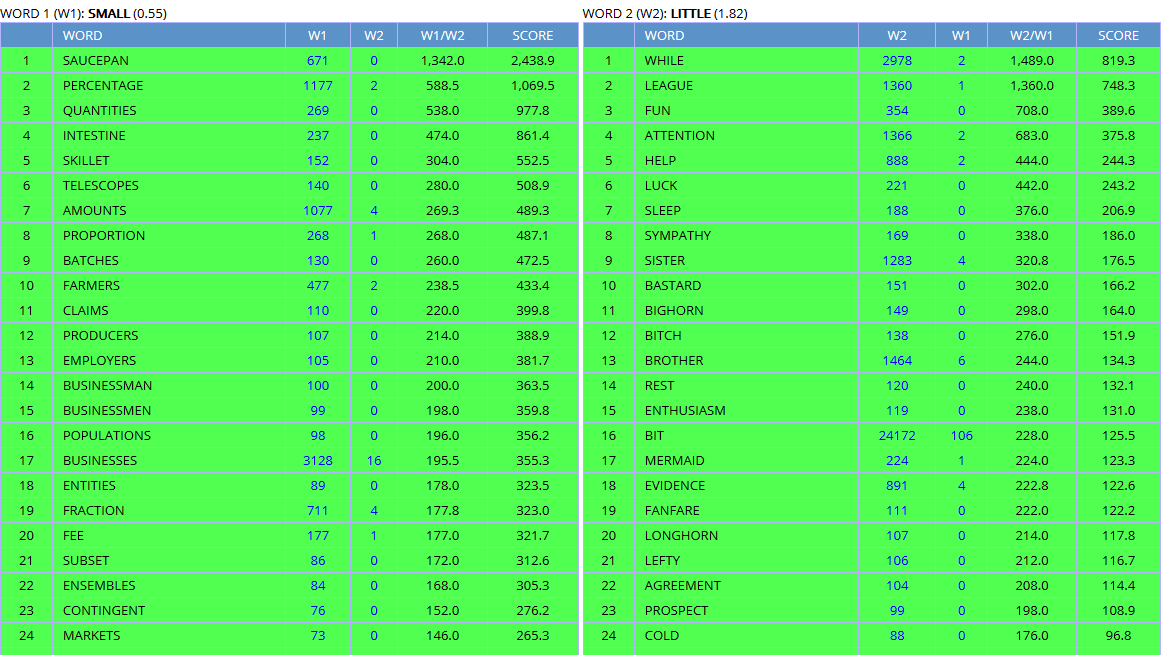

What is “safer” with such corpora is that the data they contain have been carefully controlled and edited, that is to say some thought has been given to whether they were representative of a specific variety of language. A corpus, which one could define as a collection of machine-readable authentic texts (including transcripts of spoken data) which is sampled to be representative of a particular language or language variety and which may be annotated with various forms of linguistic information (see Corpus-Based Language Studies: An Advanced Resource Book, by Anthony McEnery, Richard Xiao, and Yukio Tono), contains only a sample of a specific language variety. For instance, the COCA does not contain all American English words written and spoken between 1990 and 2015, but a careful selection has been made by the designers of the corpus to include different registers and a sufficient number of texts to make it a balanced corpus that is meant to be representative of what standard American English is. Such caution has not been taken for the Google Books Corpus (but once again, the tool does not claim it is an electronic corpus that is comparable to the BYU corpora), and as a consequence, the results provided by the COCA, the BNC, or the NOW corpus can be trusted with more confidence (Note that the BNC contains data from the 1980s and 1990s and is thus getting “old” but the Written and Spoken BNC2014 project is on its way). Also, with corpora like the ones to be found on the BYU website, searches can be more sophisticated, as the corpus has been annotated, POS- tagged (POS for “parts-of-speech”), that is to say each word is associated with its grammatical category, allowing you to perform searches like the kind of adverb that modifies the verb recommend for instance, the kind of nouns that can be modified by small or by little, or the kind of nouns that can be associated with phrasal verbs that have multiple meanings like e.g. go off (see screenshots from the COCA below). The Google Books Corpus does make such requests possible (see About Ngram Viewer page), but options are much more limited and the interface is not as user-friendly as the BYU corpora website. Note however that some GBC samples have been extracted and made available for use with the BYU interface, for American English (155 billion words), British English (34 million words), Spanish (45 billion words).

There are many reasons why a professional translator would want to use such monolingual electronic corpora (in addition to translation memories, which are aligned bilingual parallel corpora, or online parallel corpora on www.linguee.com or http://context.reverso.net/translation), in order to collect information on the attested use of words, expressions, or grammatical constructions in context, on geographical and register variation, on collocation and semantic prosody phenomena. With such huge linguistic databases, much more information can be collected than in traditional (including online) dictionaries or grammar books. Electronic corpora are meant to complement the information to be found in such traditional tools by providing hundreds or thousands of real life, attested examples in context as well as frequency data and register/geographical distribution. This approach is more and more common these days in foreign language teaching and is known as data-driven learning (DDL), providing interesting results with students. Translators are not always very familiar with electronic corpora, generally for lack of training, but there are now many books on the subject, e.g. Federico Zanettin’s Translation-Driven Corpora: Corpus Resources for Descriptive and Applied Translation Studies (2012), Corpora in Translator Education by Federico Zanettin, Silvia Bernardini and Dominic Stewart (2003), Corpus Use and Translating, edited by Allison Beeby, Patricia Rodríguez-Inés and Pilar Sánchez-Gijón (2009), or my own (in French), La Traductologie de Corpus (2016) – sorry for the product placement. There are also regular workshops nowadays on the use of electronic corpora for translators at universities, as well as specific classes within translation programs. Some websites provide access to corpora with user-friendly interfaces, like the BYU webpage or the very rich, multilingual Sketch Engine website (although this one requires a subscription). As a consequence, and with the big data revolution going on, we can expect the use of electronic corpora by professional translators to increase, and not only the Google Books Corpus, right? ;o) Speaking of the GBC, if one compares the results provided above for the different possibilities of referring to the influenza endemic to birds with results from the COCA and the NOW corpus, differences can be observed, with bird flu showing a higher frequency (all frequencies are per million words) than either avian fluor avian influenza (note that the COCA results include all registers, written and spoken, which makes our results not completely comparable between them).

Naturally, translators might feel frustrated that the official corpora mentioned here contain language that is too “general” in comparison with their technical, specialized translation projects, but you should know that it is now very easy, quick (not to mention free!) to compile your own domain-specific corpora (insurance contracts, instruction manuals, medical reports, legal or administrative documents). These are called DIY corpora (for “do-it-yourself”), which can be compiled manually or automatically, and then be used thanks to specific software called concordancers, like AntConc for instance. But that’s another story, isn’t it?

I would like to thank Professor Mark Davies for allowing me to use screenshots for this blog post.

I recently read a blog post on The Open Mic that describes lesser-known free online tools for translators, among which The Google Books Corpus and its Ngram Viewer was listed. Although I am an extensive user of electronic corpora and, as a translation trainer in the specialized translation program of the University of Lille, France, I teach my students how to use electronic corpora for their translation tasks (some of my colleagues even call me the “corpus guy”), I am no big fan of the Google Books Corpus as a linguistic database providing translators with relevant linguistic information for their translation projects. Especially as we have much better electronic corpora that are available online. Not that the Google Books Corpus is not a great tool, but professional translators searching for linguistic information have more sophisticated, better quality electronic corpora at their disposal, as user-friendly, as accessible, and as free as the Google Books Corpus.